Circular Kenya: when the magic happens

A discovery journey into community-led circular innovations

With Wekesa Zablon Wanyama

Ladies & Gentlemen, welcome on board of Circular Conversations Airlines! The host (H) speaking, message to all passengers:

We are about to embark on an adventurous journey through the daily life of Nairobi, to discover the opportunities and challenges Kenyan individuals and communities are encountering along the road to a prosperous life; for the local society, environment and economy. This is a journey into the potential of community-born and -led initiatives that try to reshape local socio-cultural and economic norms, with the ultimate objective of creating healthier, wealthier and more connected communities. We will see the good and the bad, the beautiful and the ugly, the inspiring and the frustrating, but will strive to highlight what our journey guide, Wekesa Zablon Wanyama, defines as “the moment when the magic happens”.

Wekesa (W) is a young Kenyan designer and community leader and Kenya’s Regional Organizer for the African Circular Economy Network. As a designer born and raised in Nairobi, he leads Circular Design Nairobi, a source of empowerment for design communities in the region to unlock the paradigms and embrace the new tools of transforming enterprise ‘to realise the promise that lies unexploited’. With a passion for improving education for children and (young) adults, Wekesa is engaged in a multiplicity of initiatives aimed at making individuals entrepreneurial and aware of the potential of circular practices.

Wekesa

Through the eyes and voice of Wekesa, this journey will shed light on local circular opportunities, their socio-economic and environmental potential, and the pressing challenges to their large scale adoption and reproduction. Through multiple case-studies, we will uncover how significant problems are being tackled through effective interventions and how these might be scaled up to provide benefits across the country and the whole continent. This journey has a flavour of real life, as crude as it gets, because it is not in fairytale but in reality that the magic happens. We will be exposed to a variety of stories and narratives, uncovering deep conflicts of interests, cultural norms and social practices. Ultimately, it will be you as a reader deciding which story to embrace and share.

The final destination is as yet unknown, but the journey is with the following stops:

Welcome to Nairobi: a city of multiple faces

Community-led circular initiatives

Seizing opportunities through circular interventions

The challenges on the way

Circularity in the everyday life - selected cases

Last stop: A community-based circular economy

Dear circular travellers, we are ready for take-off. Are you?

Chapter I. Welcome to Nairobi: a city of multiple faces

Known as the “Green City in the Sun”, due to the Nairobi National Park that lies at the doorstep of the city, Nairobi is a city of many faces and many stories. As our journey guide, Wekesa, stresses himself, “there are so many different lives you can live in Nairobi, from the most exotic and hedonistic life until the most basic one”. As capital and largest Kenyan city, Nairobi is the pulsating heart of the country’s economic, cultural and financial activity. Hosting many universities, government institutions, international organizations and multinationals, the city exerts a great appeal on young Kenyans and foreigners who come here in search of employment opportunities.

“They estimated that when you get to Nairobi, you’ll have to stay 20 years before you can go back to a rural area or to another location”.

Nairobi is the place of ambitions and a clear manifestation of two current trends common to many African countries: increasing standards of living and increasing urbanisation. With an estimated population of around 5 million people (6.5 in the greater metropolitan area), which is expected to reach over 10 million by 2030, Nairobi is an always-expanding city, which hasn’t yet managed to build up the city’s infrastructure to be able to accomodate the rising demand for housing, basic services and roads and still lacks key infrastructures, especially in mobility, waste management and water management.

This lack of infrastructures has resulted in a substantial part of the population—UN Habitat 2013 talks of 60%—living in informal, low-income settlements and having difficult access, if at all,to basic services. Even though poverty levels have been steadily decreasing over the past years—from 46% in 2006 to 36% in 2016, African Bureau of Statistics—a considerable amount of the residents still live under the poverty line, with estimates in Nairobi that talk about 30%. From aerial pictures of Nairobi, as testified in the project Unequal Scenes by American photographer Johnny Miller, it is evident the different lives and conditions that this city offers. A city of multiple faces.

Johnny Miller, Unequal Spaces - Nairobi

Johnny Miller, Unequal Spaces - Nairobi

Johnny Miller, Unequal Spaces - Nairobi

Johnny Miller, Unequal Spaces - Nairobi

Nairobi is a vibrant, multi-cultural and tolerant city that has been acquiring a status of national and regional economic and cultural hub for Kenya, and even for neighbouring countries. Its population is highly ethnically-diverse, with all Kenyan ethnic groups and international expats living together. For the youth coming from rural areas or displaced countries, Nairobi is projected as the land of opportunity.

H: After this intro, let Wekesa do the honours as our journey guide and local Nairobian. Wekesa, how is life in Nairobi?

W: “Nairobi is a really fast-moving town. Most of the residents in Nairobi are on rent property, with almost 90% of the city-dwellers renting property. Nairobi is one of the most expensive cities in Africa for property. In terms of mobility, we don’t have a public transport system, but a private-public arrangement, which doesn’t cover the whole city, and 60% of the people simply walk. Nairobi is a quite complex value chain. When you look at possibilities for intervention in mobility, waste management and other infrastructures, there are so many actors that need to be engaged; it is quite complex. Before we were running a centralized system, so most of the resources were placed in Nairobi.

“Nairobi is a quite complex value chain”

Demographically, you have a lot of people that are in the age range 18-35, moving to Nairobi trying to seek education and start their careers. They estimated that when you get into Nairobi, you’ll have to spend 20 years before you can leave the city and go back to rural areas or another location. It is a growing university city, population of 5 million at night and close to 7 million during the day. It is a uniquely placed city, most of the freight has to pass through it. Traffic-wise it can be a mess, but now they are trying it to move it out of Nairobi.”

H: And what about the social and cultural atmosphere in the city?

W: “Culturally it is a vibrant city; you can imagine what the convergence of all those young people in the city does in terms of cultural and socio-economic diversity. Many people are living in low-income settlements, and even with all of that, most of the companies choose to HQ in Nairobi in East Africa. The government is planning to unleash Nairobi as a financial capital of the region, and we have a lot of start-ups that are settling around here, most of which are expats. Nairobi is super vibrant, we hosted the Sudanese government and the Somalian governments when there there the transitions in those countries, refugees from Congo, businessmen from Rwanda, Burundi, Budan, people from Ethiopia. There is a joke around here that says “people who enjoy life the most in Nairobi are not Nairobians, but are foreigners”.

Chapter II. Community-led circular initiatives

At the core of this journey are community-led initiatives, ideated and started by members of the local community, with the objective of creating social interactions to realize social, economic and environmental goals in their local context. The focus is posed on initiatives related to the circular economy and to the construction of a development model able to produce economic value, but not at the detriment of social and environmental considerations. These community initiatives are an act of self-empowerment and self-determination in the transition towards a more circular, equitable and accessible socio-economic system.

W: “In this context, it is incredibly useful for us to start now the conversation about circularity and the impact it has on our communities. We need a language that can invoke citizens’ action. A principle like keeping materials at the highest value possible is not easy to get at the backdrop of all the advertisement we are subject to. The nudges that are crafted in advertisement just get people to consume. When it comes to awareness, just being able to communicate some of these principles so that the citizens can internalize them is of ultimate importance for designing out waste in our lifestyles”.

A central goal of community initiatives is to create awareness with the objective of promoting and incentivizing more sustainable behaviour, lifestyles and social practices. In this respect, the main challenge is to understand which narratives and discourses can communicate valuable information, trigger citizens’ action and bring about participation and behavioural change.

“We need language that can invoke citizens’ action and provide incentives for individuals to go an extra mile.”

H: We will certainly have the opportunity to explore it during our journey, but, as a preamble, what is the value of community-led initiatives? Why are they key to the creation of a better future?

W: “We have hierarchical systems associated with multinationals that are coming in and putting up systems. To counteract this, we have had communities that have been organized around circularity for a long time. The need for community involvement becomes evident when you look at systems like recycling, where you have several ecosystems that are distributed across several locations, and the only way to get those resources is to get some kind of community where everybody feels safe to share these resources, an environment that enables both collaboration and competition. Making people communicate is essential in taking the frontier in circularity. We have a number of case-studies that have been successful and it has been through cooperatives, also with public transport.”

H: Let’s come to a first practical example relating to the circular economy. Can community initiatives and practices empower individuals to start circular businesses?

W: “In terms of financing the circular economy, the community comes in in so many ways. Look for instance at co-ops called SACCOs or Chamas and the role they have played in setting up indigenous businesses. They can have a great impact when you look at the future of that in terms of setting up circular enterprises, pulling up resources and re-orienting people’s mindsets. If you look at neighbourhoods, the idea of coming up with neighbourhood alliances is imperative. One of the opportunity areas that we need to pursue and discuss when we talk about Sub-Saharan Africa is the role of cooperatives and communities steering us into the future of delivering goods and services.”

“The role of cooperatives and communities steering us into the future of delivering goods and services”

The potential role of SACCOs as a financing tool for the set-up and scale-up of circular businesses is highly relevant if we look at the pivotal function that cooperatives have been playing in Kenya’s socio-economic dynamics. It has been estimated that around 63% of Kenyans earn their livelihood from cooperative enterprise, accounting for 45% of GDP. The term SACCO, which identifies those co-operatives, stands for Savings and Credit Cooperative, which provides financial services to its members, such as the mobilization of funds for investment purposes and the provision of affordable credit. One of the valuable functions of SACCOs are to incentivize and use collective savings to promote investments in business and property for its members. SACCOs are also called Chamas, where Chama is the Kiswahili word for “group” or “body”. In Kenya, there are estimated to be more than 300,000 chamas managing a total of KSH 300 billion (USD $ 3.4 billion) in assets.

Chapter III. Seizing opportunities through circular interventions

In its work, Wekesa focuses on three main areas:

Awareness of circular economy model and behavioural change: working together with schools to engage young learners, introducing them to a different economic model and behavioural patterns, and incentivizing them to come up with circular ideas and initiatives for the local community.

Community Design: pushing community designers to rethink the provision of basic necessities for the local population, especially for those at the bottom of the pyramid

Direct engagement with households: building a direct relationship with households in order to work together to find shared solutions in different areas, with a focus on waste management.

This chapter illustrates in detail some of the interventions Wekesa has been working on in these three macro-areas.

Intervention #1. Community designers transforming value chains

As a designer focusing on community challenges and opportunities, Wekesa is constantly on the outlook for circular solutions that might address severe problems and empower the local community. To create a place for fruitful exchange and collaboration, Wekesa has been working on the establishment of a community of designers having open conversations about how to rethink value chains and the provision of services and goods to the local residents. Re-designing the provision of economic services and the way human needs are satisfied is a crucial principle of the circular economy, and, in this respect, circular interventions offer invaluable opportunities to increase accessibility and well-being in the economic system.

H: What does the circular economy mean to you as designer involved in the life of a community?

W: “As a designer, knowing about the circular economy and developing those skills necessary to navigate the transition from linear to circular gives me a lot of responsibility, but at the same time also a lot of freedom. Initially I felt as a designer I was just free to come up with stuff, without deep knowledge of the context around. RIght now, I am a cautious of the team that I work with, of the surrounding ecosystem and I think about the implications of the interventions that I am working on. My impact as a designer to a certain community is that I design some solutions for it and I am able to quantify it, and say whether it’s positive or negative. I should be able to sleep at night when I design a solution given that I know how powerful designers are in terms of shaping preferences, influencing choices, and creating desirability.”

“I know how powerful designers are in terms of shaping preferences, influencing choices and creating desirability.”

H: What is your strategy for operating in this space?

W: “The way forward for us is to work with designers who are distributed along different value chains of certain products. For instance, we work with factory designers, packaging designers, designers working with raw materials and those working directly with communities. Then, we invite young learners and have a conversation all together about what we see as opportunities in the transition from linear economy to circularity. We are super interested to start with value chains that have upstreams and downstreams and that are visible and have potential for impact, especially in relation to locally produced and consumed products.”

H: What are your goals through this intervention?

W: “We hope that with this approach we will be able to accelerate the transition to circularity through collaboration and community projects. The design community in the region is not as big, but that’s where we see the opportunity to intervene and start with some touch-points that have the potential for impact and drive meaningful conversations on packaging, product distribution, energy distribution, resource use and regeneration. One conversation that I feel we need to have on a community level is how can we, as community designers, come up with solutions about all this technology that is being dumped. We are super thrilled and open to new approaches for finding ecosystem solutions”.

“We hope that with this approach we will be able to accelerate the transition to circularity through collaboration and community projects”

Intervention #2. Creating awareness and changing behaviour in young learners

The second focus-area Wekesa has been working on is engaging and working together with young learners in order to create awareness on the benefits of the circular economy and the adoption of a sustainable lifestyle.

H: In essence, why is it so important to engage young learners and create this awareness in relation to the circular economy?

W: “Kids of school age have a huge potential to influence behavioural and cultural change, but only if done properly. In our context, kids belong to the community most of the time, they are super open and they are also in the position to influence adult behaviour, like ‘hey dad, why are you buying a new phone, instead of repairing the old one?’”

H: From a practical viewpoint, how do you introduce young learners to the conversation about circularity?

W: “We are currently partnering with organisations to develop learning and teaching modules for educators and young learners to be able to navigate that space. We are looking to design these educational modules, and we can go anywhere. A great opportunity is to teach young learners how to get into circularity and to do so while using a technology like augmented reality or virtual reality, gamifying the whole thing. There is huge potential around that space when it comes to behavioural change, and we are moving into it.

H: What is your educational approach?

W: “The way I approach the circular economy with young learners is informed by what happens in the environment around us. We did some preliminary studies observing the behaviour behind traffic accidents, waste, littering and it all trickles down to the way young learners behave. We saw an opportunity for young learners to be at the centre of behavioural change and we are exploring ways in which we can design nudges that can be implemented in schools. In terms of micro-interventions, we organize trips for young learners to learn about recycling, visiting companies that are doing exceptional work, mostly around upcycling. We are constantly looking at how to create a language that is super understandable and can speak about what circular is and inspire young people. Through my conversations, I keep getting a running theme: working with schools to build the foundations for responsible consumption.”

“Working with schools to build the foundations for responsible consumption”

Going exactly in this direction, Wekesa has been working on a project inspired by Educate! Developing Young Learners & Entrepreneurs in Africa, which proposes educational modules to introduce circularity to young learners and push them to start applying circular thinking in the school setting. Through an horizontal and interactive learning model, young learners are pushed to: identify the urgent challenges that finite resource pose to Kenya’s economic system, discuss our current consumption and production patterns, formulate campaigns that will get the community to be aware about circularity, and propose better ways to manage school waste, pointing out challenges and opportunities of switching to circularity. By providing a critique of the linear economy, and comparing living systems with man-made systems, these modules aims at making young learners active participants in the adoption and diffusion of this alternative economic model: the circular economy.

W: “On a high level, we are exploring the steps to create a space of empowerment for young learners who have strong potential. We need to break down the information in a very simple way that is understandable, and we must remind that we have to communicate a message of hope. We are looking at leveraging augmented reality and virtuality reality, and coming up with simple but fun and dreamy experiences that young people can go through to create the world the need. In this way, they will feel empowered and feel that this is something that they can be able to achieve.”

H: Before you mentioned some of the micro-interventions you have been working on, such as formative trips with young learners. Any particular one you would like to share?

W: “Let me share with you the story of the Ngong field trip. Three quarters of the participants were students from different disciplines, notably from the design and environmental clubs of the various universities. The N’gong settlement has a fair amount of lush and is one of the greener towns in the region. Powered with its own wind-generated electricity, Ngong hills was voted as the most romantic spot in Kenya in 2016. This team helped us map out some of the problems that the residents were facing around waste management.

One group visited a fresh food market and the town’s landfill and found that the authorities and residents were having challenges putting organic waste to good use. Organic waste formed a notable percentage of the waste in the landfill. The group walked uphill to examine the effects of plastic waste on the environment, observing that a lot of waste was being dumped in roadside hedges in an otherwise beautiful landscape. This was a design walk that traced the path of plastics consumption. By following the path of plastics from usage to landfill, the community was changed. It provoked them to see plastics in so many forms and uses where it was previously always unnoticed”.

H: And, lastly, any inspiring event about circular design you have been to lately in Nairobi?

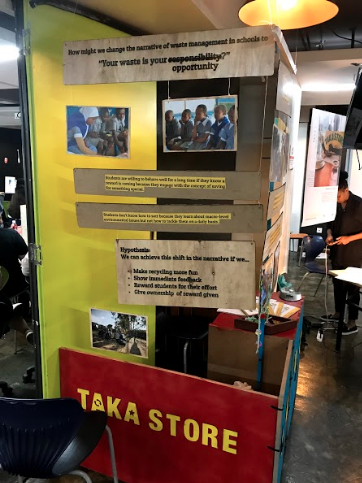

Work by students from the Nairobi Design Institute, during the Goglobal 2019

W: “At a circular design research level, I have been able to participate to a number of design exhibitions. One was with the Nairobi Design Institute and it was about working with young learners to change behaviour. I include a photo on that particular intervention; it’s about rethinking systems that work around waste and how young learners can contribute to that. It’s not my personal work, but an exhibition I attended and learned from.”

Intervention #3. Direct engagement with communities and households

The final area Wekesa has been focusing on is directly engaging households in order to find shared solutions to mounting problems, such as waste management. The objective of this intervention is to promote a more circular ecosystem around the collection, management and transformation of waste.

W: “The last intervention we are working on as an organization is working directly in communities and households. Due to failures in infrastructures, what we have for waste collection is done informally; there is no sorting and everything is being thrown in one basket. There are hardly any incentives for people to go an extra mile and sort it properly. Most of the households are giving away a lot of valuable stuff that could be kept at high value and be distributed. So we are looking at how to get into that space and open up operations at the household level”.

“Most of the households are giving away a lot of valuable stuff that could be kept at high value and be distributed”

H: What are the challenges to start operating in the waste collection and management space?

W: “This is a space that is hugely informal and they won’t give you the opportunity to get into that space; it’s like a cartel movement. We are looking at the best ways to intervene and reach households. In a city like Nairobi it is problematic to involve households. You can start small, in certain locations, opening up that conversation in households, communities and neighbourhoods. The challenge comes because every community has its own language and its own collectors, and the collectors that are where I live might not be the same ones that work one kilometer away from here. This means that we need to renegotiate again with those collectors and get households in the conversation. But working on challenges is a thing that we are super curious to set up and explore”.

H: Which types of waste have you been focusing upon?

W: “ One thing with households is they get to start separating waste, so the main focus right now with households is to come up with the adoption of good behaviour. We are looking at food waste, organic waste, plastics, paper,glass, and e-waste. Our focus at the moment is on e-waste--because it’s hazardous--safe plastic waste disposal, and waste separation. We are looking at waste separation, with an interest in making sure that electronic batteries and all those hazardous materials are not mixed with other waste, like food waste, because that is what we feed to the pigs in the city. Right now, waste is sorted post-collection in sorting stations on the side of the road or at the river, and some of the waste that cannot be taken to landfill, ends up leaking into the environment. That is really alarming and I prefer that waste is sorted out in households and is collected already sorted and channelled directly to the transfer stations. Coming up with infrastructure for that is something that we are looking to set up”.

H: Talking more broadly, what are the opportunities coming with a large-scale adoption of the circular economy in Kenya?

W: “For me, these three interventions—redesigning value chains, working with young learners and reaching households—are what I feel can do the magic in the context of Nairobi. The magic happens when we come up with solutions that provide basic necessities to the people at the bottom of the pyramid. One specific opportunity we can look at is developing skills and incentives to repair electronic waste, or even redesign consumption completely. Right now, when it comes to appliances that are bigger and more expensive, there is an incentive to repair and for people to learn these skills. But the same is not valid for electronics that are of lower price. If consumers make that shift, those skills would become an important driver for jobs.”

“The magic happens when we come up with solutions that provide basic necessities to the people at the bottom of the pyramid”

Chapter IV. The Challenges on the way

After having explored some of the abundant opportunities that accrue when circular economy thinking is applied to community problems, it is now to time to discover the challenges on the path towards a regenerative and distributive economy. As in many other parts of the world, the challenges to circularity in Kenya are still many. On the one hand, there are structural deficits, especially in terms of waste management, water management, provision of (clean and renewable) energy, and mobility. On the other hand, there are cultural considerations, with the growing influence of advertisements away from traditional values towards consumerism and status-seeking consumption behaviour. Here, Wekesa focuses on two challenges: the cultural effect of advertisements and the repair-repurchase tradeoff.

Challenge #1. Advertisement & consumerism

As disposable income and population levels have both been quickly rising in Africa, big multinationals are looking at the African market as the next land to conquer, having at their disposal the powerful army of advertisements: on tv, on buses, at stations, and around streets. The trend is certainly not a novel one. With greater exposure to social media, advertisements and range of products available, people’s desires and preferences change. In this changed context, ownership of products becomes a strong determinant of social status and position in the local community. This pervasive attitude reaches kids and finds in them an often-recurring manifestation in a sentence such as: “I saw that on TV and I want it”.

W: “Community initiatives are missing out on exposure to social media and advertisement, and we now start feeling that this kind of good behaviour is clichè. I give you an example of Coca-Cola, which sells soda both in plastic and glass bottles. Given that soda sold in glass is cheaper, if you go to shop with a glass bottle, people would say ‘hey, you are poor, you can’t even afford a plastic bottle’. Most of these communities, especially low-middle income communities, feel like the amount of money you consume on stuff gives you status.

“Are you going to repair your blender? No, throw it away and buy a new one”

“Who repairs a phone screen? It’s broken!”

This kind of fad is breaking the genuine. What we need to do right now is to make sustainable behaviour desirable.

How do we do it, especially for young people? How do we move away from propagating this narrative around young people that if you consume a lot you are hurting the environment to one narrative in which if you consume less you are making your life better? How do we reframe the way we reach our citizens to give them hope? How do we reward good behaviour? We are exposed to a lot of advertisement that says that consuming will give you joy. My brother has a 9 years old daughter, and I have been with her to a supermarket and she was just crying for stuff, ‘daddy I saw that on TV and I want it’. This kind of advertisement changes the consumer mindset very early on, and there is no regulation for it.”

“What we need to do right now is to make sustainable behaviour desirable”

This is the battle of narratives. On one side, the narratives coming from participatory and impactful community initiatives, which try to redesign entire value chains and services for the sake of locally-distributed socio-economic benefits. One the other, the narrative of consumerism being divulgated by large multinationals with the power of changing consumers’ preferences and behaviour, towards an increased tendency to purchase new products.

Wekesa’s example of the plastic Coca-Cola bottle as a social-status symbol echoes Adam Smith’s case for the linen shirt, which became a necessity in Europe in the 18th century, such that “a linen shirt is, strictly speaking, not a necessity of life...but the poorest creditable person of either sex would be ashamed to appear in public without them” (An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Book 5, chapter 2). In the context of our days, this battle of narratives represents a serious and intricate challenge to the ideation, realization and propagation of circular practices. If a single-plastic bottle or the newest electronic appliances become the linen shirt of our days, such that not having them would cause us shame in social interactions, then the road to circularity will be a very difficult one.

Challenge #2. Repair-repurchase tradeoff for electronic goods

The second challenge identified by Wekesa relates to the comparative price of repairing vs. buying a new appliances, depending on the type of appliance and original cost. Repairing appliances for re-use is a circular practice and an increase of repairing activities would push the local economy and create an employment demand for those skills, contributing to higher employment levels.

W: “The bigger electronic appliances, like fridges, are repaired, refurbished and we get them in households, because the price range is high. If you are buying a product for more than 300 dollars, then you feel you need to repair it. There is a huge appetite for people to learn repair-skills for this kind of technology. But if you are getting anything below 100 dollars, then the benefit of landing and buying a new one might be perceived as higher. Say you got something for 100 dollars, then after 6 months it breaks and repairing costs 20 dollars, so you are thinking: should I repair it or should I go for another one, the newer one, that is 60 dollars? So, you see a lot of oscillation around our commitment with e-waste, and for us that is a great opportunity for consumer awareness, for consumer education, or direct investment in terms of how we take it forward as a circularity opportunity. So, what can we do with that?”

This question is, certainly, a relevant one. Which measures can be put in place in order to increase consumers awareness about e-waste and provide more incentives for repairing? If one option at the institutional level is certainly represented by a tax discount on repairing services, the issue is still open in terms of ways to address consumers’ behaviour and awareness.

Chapter V. Circularity in the everyday life - selected cases

It is now time to get immersed in the quotidian life of Nairobi, being exposed to a series of case-studies about cooking-oil, milk ATMs and informal food vendors. Before delving into these cases, however, a quick snapshot of the local context of the Nairobian economy. Since the late 1990s, the concept and practice of the kadogo economy has gained prominence in Kenya. The key idea of the kadogo economy is to sell products in smaller units in order to make food purchase accessible for low-income earners. In those years, as a reaction to growing poverty in Kenya, manufacturers and sellers started packing smaller units of a product not to lose that market.

As economic logic would suggest, and as a recent study found out, buying in smaller quantities comes with a premium. This means that in the cost-to-quantity ratio, low-income earners come out in a position of disadvantage relatively to higher income earners. That is, they end up paying more for the same unit of a good. Despite the economic fact that buying in smaller portions is not financially convenient, the kadogo economy has been playing a fundamental role in the life of low-income earners.

H: What is your viewpoint on the role played by the kadogo economy?

W: “The kadogo economy has been empowering the low-income earners in terms of cost and availability. The kadogo economy exists out of need, because people need to consume products and most of the low-income market is not served by major brands. The challenges come with brands coming in and competing to impress consumers and conquer the market, without much consideration for the environment and fair work. The job is usually done by marketing agencies that come in to create that market where to launch the product. Very little thought is put into product development, such that products are not designed for the market, they are imposed upon it. You see the logic behind it in advertisements. These ads cover East and Central Africa and run on tv throughout the region, with just a translation of the language, allowing to lower the costs of production. For these companies, the priority is to have targeted marketing to increase brand awareness, so the bulk of the budget is in marketing, not in product development”.

“Very little thought is put into product development, such that products are not designed for the market, they are imposed upon it”

H: From these words it appears as multinationals are doing the wrong kind of kadogo economy. If it is so, what is the right sphere of action around the kadogo economy?

W: “ The opportunity in the kadogo economy is thinking and centering most of the market approach in product development rather than marketing. Whenever there is a budget for development and innovation, great discoveries can be made. Brands can learn a lot from the kadogo economy, but I think that it has been hijacked by the media brands, because they want shortcuts, incremental improvements rather than a disruptive one, like a cooking oil dispenser. The challenge is that cooking oIl dispensers are costly, so the beneficiaries of this kind of set-up are not necessarily able to afford these costs overhead. So, I would say that the kadogo economy offers us a lot to learn from, but the hijacking of the kadogo economy by big brands is making a mess out of the whole situation.”

From these considerations, we see that the main opportunities offered by the kadogo economy are to completely rethink delivery systems of basic goods, especially through the use of automatic dispenser that go without packaging. The danger, instead, is represented by the aggressive market entry of big brands eager to conquer this market with the best ad.

Case #1. Cooking Oil

The first case strictly relates to the challenges and opportunities in the kadogo economy, and is about a basic good for culinary preparation: cooking oil.

W: “This is something I discovered only recently. At the supermarket, if you buy a bottle of 5 liters of cooking oil, you will spend 5 dollars. If you buy 2 liters, you will spend 2 dollars. If you buy half a liter, you will spend 1 dollar. Now, this retailer figured out that buying 20 liters would cost 10 dollars. So, he buys 20 liters and charges 60 cents for half a liter (instead of 1 dollar), and there is a huge market for it. There is a great potential to formalize it and introduce dispensers, like ATMs”

H: And what about the challenges on the way towards a more diffused adoption of automatic dispensers?

W: “The only challenge is that they are not community-owned enterprises, they are multinationals that have processed lines. There was this joke saying that companies that package water are in the plastics business, not in the water business (laughs)! The kind of packaging in informal, low-income communities are multi-use, because if I invest in half a liter of cooking oil, I might buy one and use that one for the longest possible. Then, if one day I have a lot of money, I will go and buy a three liter one. There are already a lot of case-studies around the avoidance of single-use packaging and they should definitely be encouraged”

Case #2. Milk ATMs

Milk ATMS are a case of what rethinking delivery systems can do in terms of cutting out packaging while making a good widely accessible, also to the lowest sections of the population, the ones at the bottom of the pyramid.

W: “ In Kenya, we used to have unprocessed milk; the sale of unprocessed milk was occupying the largest percent of the market, and the packaging and cost of processing milk was making milk super expensive. From 2013, there was this cause to explore how milk ATMs would work, but at the same time it was immediately recognized that these machines were very expensive. The cost of the machines was making it impossible for farmers to get into that market, but thanks to co-ops or SACCOs farmers have been able to raise capital and invest in this kind of vending machines, and we have seen a drastic drop in the number of milk packages or potential packaging that would have otherwise entered the environment. In households that consume a lot of milk, they’ll just rather re-use plastic bottles now. That is a space that has demonstrated what rethinking delivery systems can do. You can get a person at your doorstep with the milk, you wash your container and get the milk in there. I feel that the whole ecosystem is a nice space where we can encourage the delivery systems that cut out unnecessary packaging”

Cutting out unnecessary packaging, especially plastics, is a priority for businesses in Kenya, and also a duty as of March 15, 2017, when the Kenyan government approved a law which banned plastic bags in the country. In this way, Kenya became the second African country to outlaw plastics, following Rwanda, which outlawed them in 2008. The national plastic ban has accelerated the conversation around sustainable alternatives to plastic, which need to be equally affordable and re-usable. The default reaction from fresh food vendors and supermarket chains has been to employ paper bags as an alternative. But the true opportunity lies in completely rethinking packaging, in terms of materials, design and delivery systems. Walking on this road will also allow individuals to develop business ideas for the making and selling of reusable containers and bags.

Case #3. Food-waste prevention through informal food markets

In Nairobi, like in the rest of Kenya, the informal sector plays a huge role. Due to the social dynamics in the city—see number of daily migrants and booming youth population—informal food vendors provide to many the only caloric meal of the day, especially accommodating the nutritional needs of low-wage earners. Despite their valuable function in contributing to food security, food vendors often operate in inadequate health-sanitary conditions and are not recognized by public authorities, who often relocate them by force. A main point of concern in the case of food vendors is the conditions in which the food is stored, cooked and sold: food safety. Factors affecting food safety include insufficient sanitation facilities, inadequate access to fresh water, livestock food contamination and rapid food spoilage.

In late 2013 an informal settlements-based Food Vendors Association was founded, which since then has tried to become more active in the community and involve people in the conversation about urban food security and safety. This conversation is extremely important from many different viewpoints, as some data talk of about 80% of animal-source food being distributed through informal markets.

To set up the conversation, these might be some of the questions. How do we introduce food safety into this sector that plays such a vital role? Which kind of engagement from the side of public authorities would be beneficial? Does this sector need to transform from informal to formal? If this is the case, what are the consequences in terms of employment and food security?

Over the past years, Wekesa has been working on an intervention, a start-up concept called Jibonde Fresh, which is a fresh foods virtual hub that seeks to document informal food kiosks. Its mission is to increase the health and safety of food vendors and promote the great potential they have, by locating them and training them.

W: “What I am proud of is that we don’t have a lot of food waste. Ok, a lot of food waste happens in transportation and in farms, but when it comes to the urban areas, most of this food is sold in markets. There is a huge opportunity around that, which has been informal food markets. Informal vendors are not acceptable yet, as they are always in the run with the law, but they have paid a huge role in offsetting the food waste problems that happen with formal food markets. The biggest formal food market in Nairobi opens up at 3am in the morning, food is brought from all over the region, like bananas from Uganda, and tomatoes and oranges from Tanzania. Nairobi has a huge appetite for food; it’s a population of 4-6 millions and hardly nobody practices farming. When the food arrives at the market, after having sorted it, there is a quality test. Usually, around 70% of the food is admitted for selling, while the other 30%—mostly because of travel—doesn’t pass the test. This 30% is immediately transferred with hand-carts to informal markets, called mamamboga, which are food vendors.

H: What is the contribution that these informal vendors have in relation to making food accessible in the city?

W: “ Since 2016, when the highway was completed—opening up the city to new opportunities—we have been experiencing a real estate construction boom and, at the same time, a huge demand for food. Most of young people, between 18-35, are moving from rural to urban areas and there was a huge youth increase in cities. So you have unemployment and lots of resources unutilized, and most of the people demanding for food are either unemployed or underemployed. They are craving for food, don’t have time to go and cook at home, so they are looking for high-calories fast food, but they can’t find it cheap. Now, some of these food vendors converted into informal cook-markets on roadsides. The magic behind these informal food vendors is that they are consuming food waste and creating an entirely new value chain.”

“The magic behind these informal food vendors is that they are consuming food waste and creating an entirely new value chain”

H: So there are big opportunities also in terms of business?

W: “The hand-cart (mkokoteni) business in Nairobi is estimated at 5 billion Kenyan Shillings, just the hand-carts. You haven’t yet looked at the informal food markets, and they serve around 78% of the population, and a lot of people who earn less than 200 dollars a month. This food goes for a dollar a meal, so at least you can have a meal a day. There is an interesting opportunity around food waste and informal food vendors and how they can close the gap. I feel case-studies on circularity in Africa are often in those places that formality never reaches”.

“Case-studies on circularity in Africa are often in those places that formality never reaches”

Having identified the business potential in this sector, and being aware of the fundamental role played by informal food vendors for food security in the city, Wekesa has been working on a business idea to create value in this market, with the name of Kula Banda.

H: Wekesa, would you like to tell us more about this project?

W: “Imagine working in an office complex where the price of food per month is more than half your salary. Kula Banda offers access to trusted fair-priced food from a selected pool of informal food vendors across different locations in Nairobi by employing a mix of policy and technology interventions We deliver by bicycle saving time and energy while offering employment by tapping into the pool of young people available in the city as our couriers. Working together with city authorities and stakeholders across the food sector, we work to ensure food safety, offering security to both the informal vendor and the consumer.

We enable traceability and formalisation of the informal food vendor’s through capacity building via culinary skill classes, business development modules and linkages to clean technology from our ecosystem partnerships. We are looking at having a system that gives the vendor a bit of autonomy to be less liable for public space. One possibility is to have a public space intervention that just creates sitting spaces and enable food delivery services. In this way, food quality can be the only focus of vendors. Public spaces and placemaking are concepts that need advocacy. Now we have groups that are organizing place marking weeks in the city”

“Public spaces and placemaking are concepts that need advocacy”

Chapter VI. Final Stop: A community-based circular economy

Dear fellow travellers, we have finally arrived at the final stop of our long journey. We have had the opportunity to explore the Nairobian local context, the various challenges and opportunities around circularity, and successful interventions pushing us further in the path towards a regenerative, distributive and accessible economy. As it happens with any travel, is what a journey leaves us with once we are back home that makes the difference. And, now that we are back home, it is the time to build the future we want and urgently need.

H: Wekesa, it has been a truly inspiring discovery journey. In conclusion, tell us a bit more about your future plans. Which initiatives are you going to engage in and with what objectives?

W: “When I look at Nairobi and other cities in Africa, I see a lot of neighbourhoods that are struggling with resource management. The question is: how can we create this process that is replicable in different kinds of context? This is one of the questions that I have already started engaging with the people I am working with. In the educational space, for instance, we are thinking about how to create a design process that can be replicated. We are in the process to accelerate the transition to a circular economy and we are doing it as simple as possible, in order to eliminate any friction and make desirable behaviour fun and beneficial. My future plan is to be able to open-source most of the processes that we have so that we are able to build up exponentially. For Circular Design Nairobi, we see value in getting stakeholders to the table earlier on in the process. At a higher level, we are exploring the possibility of working with manufacturers through the Kenya Manufacturers Association to unpack the circular design guide. ”

“We are in the process to accelerate the transition to a circular economy, and we are doing it as simple as possible”

H: As a final question, and going back to the title of this journey, when does the magic happen in the context of Nairobi?

W: “The magic happens in the convergence of all the different actors. We have people who own capital and maybe feel that e-waste is an important topic and we need to work on it. Then, there are the people who work as waste pickers at a community level. The problem is that these two bodies are not connected in the ecosystem. The magic happens when informal communities manage to get well organized about waste sorting and re-use, such as using food waste for the pigs and organic waste for manure. I have seen a number of these communities and I have been super thrilled. I feel there are a lot of beautiful things happening on a community design level as opposed to a hierarchical level, where we have capital owners sitting at the top and workers sitting at the bottom. It is fundamental to be able to experience a community that is horizontal, where stakeholders are collaborating as partners in all the different stages. There are already communities that are transitioning in this way, and to use these cases and scale them up city-wide is what I see as the big next step. We need to share the incredible work that has been done in micro ecosystems”.

“There are a lot of beautiful things happening on a community design level as opposed to a hierarchical level”

At its core, this discovery journey has attempted to show exactly this: the magic of community-led circular innovations.

From Nairobi, with hope and love.

Narration and Interview by Emanuele Di Francesco

May 2019

Do you live in Africa and want to share your story of community-led circular innovations in your local context? Get in contact at circularconversations@gmail.com. Together, we’ll change the destiny of this sea!

This case-study is part of the series Circular Africa. Previous works in the series include:

A New Face for Africa - Emanuele Di Francesco

Africa, Circular Spirit - with Murielle DIaco

Biomimicry in South Africa - with Claire Janisch

Meeting Human Needs Thanks to Material Circularity - with Alexandre Lemille